Raymond Rudorff, Belle Epoque

The Dreyfus Period (1): Over View

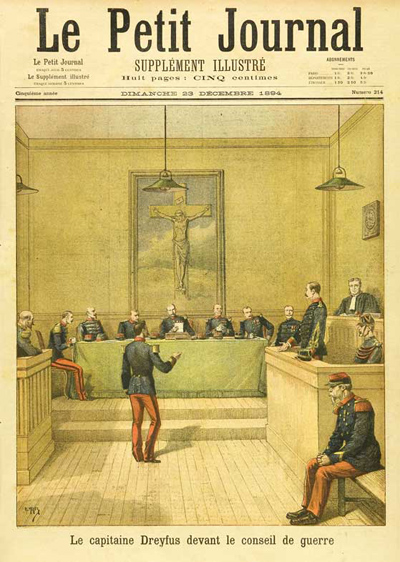

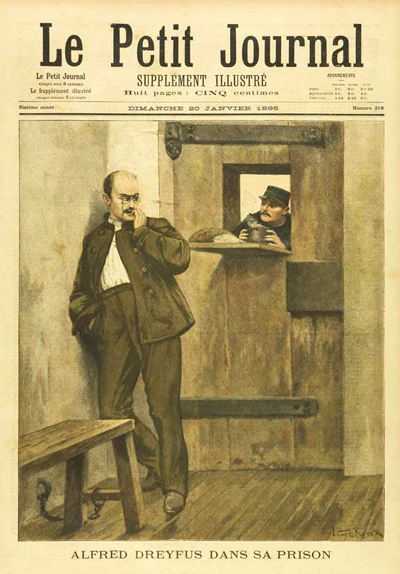

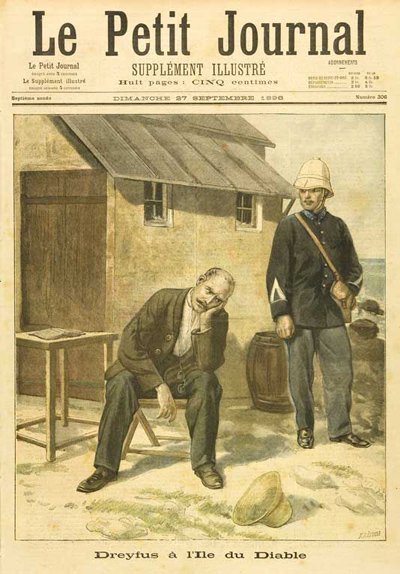

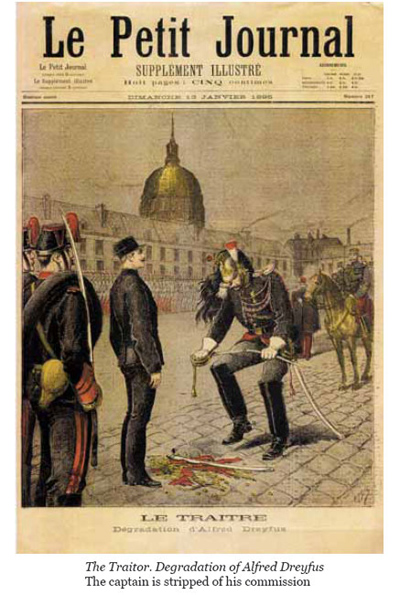

Here is a summary of the Dreyfus Affair. The accompanying illustrations from Le Petit Journal, a popular journal given to sensationalism, are evidence of the continuing fascination of the public with this story.

THE STORY of the arrest, trial, imprisonment, re-trial, pardon and final rehabilitation of Captain Alfred Dreyfus is so well known and has been told so many times that only

Dreyfus Before a Council of War |

the outlines of the affair need to be mentioned here. In October 1894, Dreyfus was a staff captain attached to the General Staff intelligence section known as the Deuxieme Bureau, and was arrested on the charge of passing on documents to the German Intelligence in Paris. A document alleged to be in his writing was produced as evidence against him. He was found guilty by a military court, and on January 5, 1895, he was publicly degraded in a humiliating ceremony before being sent to the penal colony at Devil's Island, Cayenne.

A year later, another army officer, Commandant Picquart, had begun to suspect that Dreyfus was innocent and that the evidence against him had been fabricated. A number of prominent personalities expressed their doubts about the case, contradictory "revelations" were published in the press and another officer, Esterhazy, was accused of having forged a document which had incriminated Dreyfus. Esterhazy was court martialled, acquitted and, a few days later, the newspaper L'Aurore published a sensational letter by Zola who accused ministers and high-ranking officers of concealing the truth, thus inaugurating the bitterest phase of the controversy. Esterhazy and a colleague, Colonel Henry, were arrested for forgery. In 1899 Dreyfus was brought back to France, re-tried, found guilty again, there was a fresh uproar, and he was pardoned. Calm returned to France and Parisians were able to celebrate the dawn of a new century in a comparatively peaceful atmosphere enlivened by the 1900 Exposition.

The fact that the affair had so greatly divided the nation showed

that the main issue was not merely that of the guilt or innocence

of one army officer whom many believed to have been wrongly condemned. Dreyfus himself became only the pretext for the quarrel. The question of his guilt was a political weapon used by both sides, and the reason the affair blew up to such a huge extent was because it occurred at a time in France when passions were being stirred by violent anti-Semitism, militarism and anti militarism, delirious chauvinism, anti-republican plotting and social agitation. Nothing else could have explained the remark able displays of hatred that France witnessed; it was a time when politicians and journalists fought duels regularly, when an archbishop of Paris patronised an anti-Semitic league of army officers, when writers and artists who had formerly assumed attitudes of detachment from life and world-weariness suddenly engaged themselves in political argument and propaganda, when mobs reappeared in the streets of Paris, and when society salons split into opposing factions and raucous ultra-patriots called for a coup d'etat.

The fact that the affair had so greatly divided the nation showed

that the main issue was not merely that of the guilt or innocence

of one army officer whom many believed to have been wrongly condemned. Dreyfus himself became only the pretext for the quarrel. The question of his guilt was a political weapon used by both sides, and the reason the affair blew up to such a huge extent was because it occurred at a time in France when passions were being stirred by violent anti-Semitism, militarism and anti militarism, delirious chauvinism, anti-republican plotting and social agitation. Nothing else could have explained the remark able displays of hatred that France witnessed; it was a time when politicians and journalists fought duels regularly, when an archbishop of Paris patronised an anti-Semitic league of army officers, when writers and artists who had formerly assumed attitudes of detachment from life and world-weariness suddenly engaged themselves in political argument and propaganda, when mobs reappeared in the streets of Paris, and when society salons split into opposing factions and raucous ultra-patriots called for a coup d'etat.

Dreyfus in His Prison |

Dreyfus on Devil's Island

|